Language model training is slow, even when your model is not very large. This is because you need to train the model with a large dataset and there is a large vocabulary. Therefore, it needs many training steps for the model to converge. However, there are some techniques known to speed up the training process. In this article, you will learn about them. In particular, you will learn about:

- Using optimizers

- Using learning rate schedulers

- Other techniques for better convergence or reduced memory consumption

Let’s get started.

How to Speed-Up Training of Language Models

Photo by Emma Fabbri. Some rights reserved.

Overview

This article is divided into four parts; they are:

- Optimizers for Training Language Models

- Learning Rate Schedulers

- Sequence Length Scheduling

- Other Techniques to Help Training Deep Learning Models

Optimizers for Training Language Models

Adam has been the most popular optimizer for training deep learning models. Unlike SGD and RMSProp, Adam uses both the first and second moment of the gradient to update the parameters. Using the second moment can help the model converge faster and more stably, at the expense of using more memory.

However, when training language models nowadays, you will usually use AdamW, the Adam optimizer with weight decay. Weight decay is a regularization technique to prevent overfitting. It usually involves adding a small penalty to the loss function. But in AdamW, the weight decay is applied directly to the weights instead. This is believed to be more stable because the regularization term is decoupled from the calculated gradient. It is also more robust to hyperparameter tuning, as the effect of the regularization term is applied explicitly to the weight update.

In formula, AdamW weight update algorithm is as follows:

$$

\begin{aligned}

g_t &= \nabla_\theta L(\theta_{t-1}) \\

m_t &= \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1 – \beta_1) g_t \\

v_t &= \beta_2 v_{t-1} + (1 – \beta_2) g_t^2 \\

\hat{m_t} &= m_t / (1 – \beta_1^t) \\

\hat{v_t} &= v_t / (1 – \beta_2^t) \\

\theta_t &= \theta_{t-1} – \alpha \Big( \frac{\hat{m_t}}{\sqrt{\hat{v_t}} + \epsilon} + \lambda \theta_{t-1} \Big)

\end{aligned}

$$

The model weight at step $t$ is denoted by $\theta_t$. The $g_t$ is the computed gradient from the loss function $L$, and $g_t^2$ is the elementwise square of the gradient. The $m_t$ and $v_t$ are the moving average of the first and second moment of the gradient, respectively. Learning rate $\alpha$, weight decay $\lambda$, and moving average decay rates $\beta_1$ and $\beta_2$ are hyperparameters. A small value $\epsilon$ is used to avoid division by zero. A common choice would be $\beta_1 = 0.9$, $\beta_2 = 0.999$, $\epsilon = 10^{-8}$, and $\lambda = 0.1$.

The key of AdamW is the $\lambda \theta_{t-1}$ term in the gradient update, instead of in the loss function.

AdamW is not the only choice of optimizer. Some newer optimizers have been proposed recently, such as Lion, SOAP, and AdEMAMix. You can see the paper Benchmarking Optimizers for Large Language Model Pretraining for a summary.

Learning Rate Schedulers

A learning rate scheduler is used to adjust the learning rate during training. Usually, you would prefer a larger learning rate for the early training steps and reduce the learning rate as training progresses to help the model converge. You can add a warm-up period to increase the learning rate from a small value to the peak over a short period (usually 0.1% to 2% of total steps), then the learning rate is decreased over the remaining training steps.

A warm-up period usually starts with a near-zero learning rate and increases linearly to the peak learning rate. A model starts with randomized initial weights. Starting with a large learning rate can cause poor convergence, especially for big models, large batches, and adaptive optimizers.

You can see the need for warm-up from the equations above. Assume the model is uncalibrated; the loss may vary greatly between subsequent steps. Then the first and second moments $m_t$ and $v_t$ will be fluctuating greatly, and the gradient update $\theta_t – \theta_{t-1}$ will also be fluctuating greatly. Hence, you would prefer the loss to be stable and move slowly so that AdamW can build a reliable running average. This can be easily achieved if $\alpha$ is small.

At the learning rate reduction phase, there are a few choices:

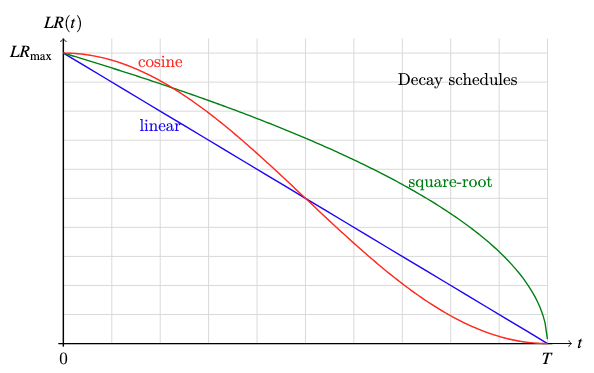

- cosine decay: $LR = LR_{\max} \cdot \frac12 \Big(1 + \cos \frac{\pi t}{T}\Big)$

- square-root decay: $LR = LR_{\max} \cdot \sqrt{\frac{T – t}{T}}$

- linear decay: $LR = LR_{\max} \cdot \frac{T – t}{T}$

Plot of the three decay functions

A large learning rate can help the model converge faster while a small learning rate can help the model stabilize. Therefore, you want the learning rate to be large at the beginning when the model is still uncalibrated, but small at the end when the model is close to its optimal state. All decay schemes above can achieve this, but you would not want the learning rate to become “too small too soon” or “too large too late”. Cosine decay is the most popular choice because it drops the learning rate more slowly at the beginning and stays longer at a low learning rate near the end, which are desirable properties to help the model converge faster and stabilize respectively.

n PyTorch, you have the CosineAnnealingLR scheduler to implement cosine decay. For the warm-up period, you need to combine with the LinearLR scheduler. Below is an example of the training loop using AdamW, CosineAnnealingLR, and LinearLR:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

import torch import torch.nn as nn import torch.optim as optim from torch.optim.lr_scheduler import LinearLR, CosineAnnealingLR, SequentialLR

# Example setup model = torch.nn.Linear(10, 1) X, y = torch.randn(5, 10), torch.randn(5) loss_fn = nn.MSELoss() optimizer = optim.AdamW(model.parameters(), lr=1e–2, betas=(0.9, 0.999), eps=1e–8, weight_decay=0.1)

# Define learning rate schedulers warmup_steps = 10 total_steps = 100 min_lr = 1e–4 warmup_lr = LinearLR(optimizer, start_factor=0.1, end_factor=1.0, total_iters=warmup_steps) cosine_lr = CosineAnnealingLR(optimizer, T_max=total_steps – warmup_steps, eta_min=min_lr) combined_lr = SequentialLR(optimizer, schedulers=[warmup_lr, cosine_lr], milestones=[warmup_steps])

# Training loop for step in range(total_steps): # train one epoch y_pred = model(X) loss = loss_fn(y_pred, y) # print loss and learning rate print(f“Step {step+1}/{total_steps}: loss {loss.item():.4f}, lr {combined_lr.get_last_lr()[0]:.4f}”) # backpropagate and update weights optimizer.zero_grad() loss.backward() optimizer.step() combined_lr.step() |

Running this code, you may see:

|

Step 1/100: loss 1.5982, lr 0.0010 Step 2/100: loss 1.5872, lr 0.0019 Step 3/100: loss 1.5665, lr 0.0028 … Step 9/100: loss 1.2738, lr 0.0082 Step 10/100: loss 1.2069, lr 0.0091 Step 11/100: loss 1.1387, lr 0.0100 … Step 98/100: loss 0.4845, lr 0.0001 Step 99/100: loss 0.4845, lr 0.0001 Step 100/100: loss 0.4845, lr 0.0001 |

Notice how the learning rate increases and then decreases.

Sequence Length Scheduling

Language models are trained with sequence data. Transformer models or recurrent neural networks are both architecturally agnostic to the sequence length. However, you may want to train the model with long sequence to let the model learn how to handle long context.

In training, long sequence lengths can be problematic. First, you train with batches of sequences, and ragged lengths mean you need to pad the sequences to the maximum length in the batch. While you will ignore the padded tokens, your model still needs to process them, hence resources are wasted. Second, in the attention mechanism, the complexity is quadratic to the sequence length. The longer the sequence, the more costly it is to process.

Therefore, you may want to create batches with sequences of similar length to avoid excessive padding.

You may also want to train the model with shorter sequences first. You can speed up the training process by quickly forcing the model to learn the patterns of the language using shorter sequences. Once the model has fairly converged, you can gradually increase the sequence length to help the model learn how to handle long contexts.

These are common techniques in training large language models to save computational resources. Note that you still set up the model with a fixed maximum sequence length, which affects how you configure the positional embeddings. However, you do not exhaust the maximum sequence length until the model has fairly converged.

Implementing sequence length scheduling means you need to write a more complex data loader to take into account of the current epoch to return the appropriate training data.

Other Techniques to Help Training Deep Learning Models

Random Restart

Training a deep learning model is a complex process and not easy to get right, especially for large models. One common issue is the model getting stuck in a local minimum and being unable to converge. Using momentum in gradient descent can help the model escape from local minima, but is not always effective. Another approach is to simply restart the training if you ever see the model fail to converge.

Random restart is the strategy of training the model multiple times from scratch. It uses different random seeds each time so that the model begins with different initial weights and different shuffling of the data. This is done in the hope that you will not always get stuck in the same local minimum, so you can pick the one with the best performance. This is ideal if you can train multiple models for fewer epochs at the beginning, then pick the best model from the pool to finish training with more epochs.

Gradient Clipping

One common issue in training deep learning models is gradient explosion. This is especially common if you train the model using lower-precision floating-point numbers, in which the range of the gradient could be too large to be represented. Gradient clipping is the technique of limiting the magnitude of the gradient to a safe value. Without it, you may see your training process suddenly fail due to the model weights or loss function becoming NaN or infinity.

There are multiple ways to clip gradients. The most common one is to clip the gradient such that the L2 norm is less than a safe value, such as 1.0 or 6.0. You can also clip the gradient to a value range, such as -5.0 to 5.0.

Gradient clipping by L2 norm means scaling the entire gradient vector if the L2 norm $\Vert g_t \Vert_2$ is greater than a safe value $c$:

$$

\hat{g_t} = \min\big(1, \frac{c}{\Vert g_t \Vert_2}\big) \cdot g_t

$$

On the other hand, gradient clipping by value means setting the gradient to a safe value whenever the gradient exceeds that value:

$$

\hat{g_t} = \begin{cases}

-c & \text{if } g_t < -c \\

g_t & \text{if } -c \le g_t \le c \\

c & \text{if } g_t > c \\

\end{cases}

$$

Using gradient clipping in PyTorch is straightforward. You can use the torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_ function to clip the gradient by L2 norm, or the torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_value_ function to clip the gradient by value. Below is an example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 |

import torch import torch.nn as nn import torch.optim as optim from torch.nn.utils import clip_grad_norm_, clip_grad_value_

# Example setup model = torch.nn.Linear(10, 1) X, y = torch.randn(5, 10), torch.randn(5) total_steps = 100 loss_fn = nn.MSELoss() optimizer = optim.AdamW(model.parameters(), lr=1e–2, betas=(0.9, 0.999), eps=1e–8, weight_decay=0.1)

# Training loop for step in range(total_steps): # train one epoch y_pred = model(X) loss = loss_fn(y_pred, y) optimizer.zero_grad() loss.backward() # clip by L2 norm clip_grad_norm_(model.parameters(), max_norm=1.0) # or clip by value # clip_grad_value_(model.parameters(), clip_value=1.0) optimizer.step() |

Mixed Precision Training

When a model becomes too large, memory consumption becomes a bottleneck as well. You may want to save memory by using lower-precision floating-point numbers in training, such as half precision (float16) or bfloat16. Compared to single precision (float32), float16 and bfloat16 can reduce memory consumption by half, but the range and precision are sacrificed.

Therefore, you may want to use mixed precision training, in which part of the model uses float32 while the other part uses float16. A common choice is to use float32 for biases but float16 for weights in linear layers.

Modern GPUs can run float16 operations at the same speed as float32, but since you can operate on more data at the same time, you can effectively run the training process at double speed.

Further Readings

Below are some resources that you may find useful:

Summary

In this article, you learned about some techniques to speed up the training process of deep learning models, especially for large language models. Specifically, you learned that:

- AdamW with cosine decay is the most popular optimizer and learning rate scheduler for training language models.

- You can use sequence length scheduling to save computational resources when training language models.

- Techniques like random restart and gradient clipping can help you train the model more stably.

- Mixed precision training can help you reduce memory consumption.